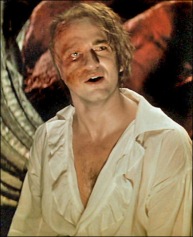

The 2004 version of The Phantom of the Opera portrays one of the most suave and attractive film Phantoms to date. Previous versions, such as the 1925 version starring Lon Chaney, emphasized the horror aspects of the story, making the Phantom monstrous and distinctly the villain (as in this still). In contrast, the musical contains a Phantom who has a more “normal” appearance physically and is an antihero–bitter to the point of criminal action, but ultimately mistreated and misunderstood by society.

Throughout both the film and stage versions of the musical, the unspoken question “what is beneath the Phantom’s mask?” is used to build suspense. At one point in the first half of the film, Christine pulls off his mask and sees the face beneath. She later describes it as “so distorted, deformed, it was hardly a face,” but the camera carefully avoids a clear view of the deformity, further tantalizing the audience. Rather than allowing the viewer to see the Phantom’s true appearance as Christine does and visualize that for the remainder of the story, the camera work serves to further distance the viewer from the Phantom as he truly is.

Finally, in the last few minutes of the movie, the audience is allowed to see the Phantom’s face. Christine’s description hardly matches reality: the “distortion” is mild, and–especially for 1870, before the rise of modern medicine and plastic surgery–hardly the stuff of circus freak shows. In the stage show, the Phantom’s disfigurement is much more severe. In one interview, director Joel Schumacher talks about the conscious decision to downplay the Phantom’s traditionally dramatic deformity. “Even though the make-up in the stage show is grotesque, and very much a copy of the Lon Chaney make-up, I felt the audience is smarter than a lot of obvious prosthetics. The Phantom is very disfigured and the right side of his face is quite tragic. Christine, however, always looks past that and views him with compassion. As she sings, ‘This haunted face holds no horror for me now / It’s in your soul that the true distortion lies.’” Alexandra Byrne, the film’s costume designer, echoes this idea: “We didn’t want his disfigurement to be horribly grotesque. It was about trying to find the real person behind the mask. We want the audience to see his attractiveness, his anger and his vulnerability.”

Hence, the entire design of the main character was built upon the idea that the portrayal of any extreme physical differences would alienate the viewer and interfere with the Phantom’s portrayal as an antihero rather than a villain. Instead of using the story to emphasize the Phantom’s humanity, regardless of his facial features, the filmmakers gave in to the very ideologies surrounding disability that they purported to speak out against.

Sources:

The Art of Writing and Making Films: The Phantom of the Opera. Accessed at http://www.writingstudio.co.za/page742.html

The Phantom of the Opera is one of my favourite films and I have thoroughly enjoyed reading your postings on it! Your discussion of the way in which the filmmaker’s sanitized the Phantom’s disability was particularly interesting and insightful. I had never really considered this until reading your post, but compared to other versions of the film, this Phantom does seem a bit more “mild” when viewing his apparently “grotesque” features. Your last sentence – “instead of using the story to emphasize the Phantom’s humanity, regardless of his facial features, the filmmakers gave in to the very ideologies surrounding disability that they purported to speak out against” – was especially thought-provoking. It seems that by making the Phantom more “presentable” to viewers, the filmmakers are insinuating that in order for viewers to identify with him, he had to become more “normal” in appearance, at least according to societal standards. This, in effect, seems to reinforce the idea of the “us versus them” in society as it almost suggests that “abled” individuals cannot relate to those who have physical “abnormalities.”

Well, when compared to the novel, he is ESPECIALLY sanatized. Heck, even the very first movie downplayed exactly how ugly he was. In the novel (hightly recommended), he was so unsightly that despite how much she pitied him, she simply couldnt look at him without withdrawing her gaze. Several times we are told that he could have been a great emperor or even “like everybody else”, as is what he wished to be, but he was simply too ugly. Then again, the thing that truly made his hideous visage pop out of the novel with such a force that even the reader was disgusted was both the format which the story took and the (VERY) expressive writing of Gaston Leroux. The description of the Phantom (Or Erik, as he is ACTUALLY called…) is at once so descriptive and probing one can feel their eyes fleeing the pages and so vauge and untelling one has no choice but to imagine a creature wholly uniqe to oneself. Ah, on the other hand, i suppose, this situation is rather similar to the route which Disney took with The Hunchback of Notre Dame (Another novel i greatly recommend), especially on the designs of Quasimodo and Claude Frollo. Claude went from an overweight, balding priest (Or, Archdeacon, as he was) to a tall, thin, and, most importantly of all, triangular judge, whilst Quasimodo went from a… well, he went from a monsterous man to a… kind, gentle man, i suppose. He used to be a perverse parody of a man, distorted in both mind and body, but, well, the kids wouldnt like that, so, despite having all ability in the world to make him the monster he was, they made him what i can only describe as “cute”. His human distortions were given a rounded edge and, truth be told, he was, truly, made “cuter.” I dont want to go into shapetheory in character design, but, i can gladly tell you, they they utilized it to its full extent, even going so far as to make Frollos hat triangular… ah! Anyhow! You must forgive me for digressing, ehem, truth be told, i have no idea what im talking about, so, yeah, forgive my intrustion. And not to mention their inside characters… Quasimodo killed people, you know? You remember that last act in the Disney movie, where he defeats an army of guards? Well, in the book, that was an army of gypsies coming to take La Esmeralda back to the Court of Miracles, and Quasimodo promptly killed them. Most of them. The remaining ones were killed by Phoebus’ hand. Hell, he straight up bashed Jehan Frollo (Claude Frollos younger brother) to pieces! But this is too dark for a kids movie, so i guess well just make him a peacefull (but still really strong), misunderstood dude! His relation with Claude changed, too… loyal dog turned rebellious teen. So strange…

…

…I did it again. Argh. Damn tis I! Back to the Phantom! Hes a monster! He kills people! Ugly outside and inside! Love killed him, thats fact!

Im sorry for wasting your time

Thanks for the insightful perspective on this film!

In the 2004 movie, the phantom actually looks like such a cutie when he’s unmasked and his wig is off! I like him better unmasked, tbh!

I kind of have an alternative view of this though, which is basically that BECAUSE his disfigurement is so tame, it was actually truly society’s fault that he turned out the way he did. Like his face really isn’t that bad, but because everyone around him made it out to be something horrible, it warped his own perception to see it that way, which actually makes it more messed up.